NEW YORK TIMES

By MARK MAZZETTI OCT. 14, 2014

(To read the story on NYT website, click here)

WASHINGTON — The Central Intelligence Agency has run guns to insurgencies across the world during its 67-year history — from Angola to Nicaragua to Cuba. The continuing C.I.A. effort to train Syrian rebels is just the latest example of an American president becoming enticed by the prospect of using the spy agency to covertly arm and train rebel groups.

An internal C.I.A. study has found that it rarely works.

The still-classified review, one of several C.I.A. studies commissioned in 2012 and 2013 in the midst of the Obama administration’s protracted debate about whether to wade into the Syrian civil war, concluded that many past attempts by the agency to arm foreign forces covertly had a minimal impact on the long-term outcome of a conflict. They were even less effective, the report found, when the militias fought without any direct American support on the ground.

The findings of the study, described in recent weeks by current and former American government officials, were presented in the White House Situation Room and led to deep skepticism among some senior Obama administration officials about the wisdom of arming and training members of a fractured Syrian opposition.

But in April 2013, President Obama authorized the C.I.A. to begin a program to arm the rebels at a base in Jordan, and more recently the administration decided to expand the training mission with a larger parallel Pentagon program in Saudi Arabia to train “vetted” rebels to battle fighters of the Islamic State, with the aim of training approximately 5,000 rebel troops per year.

So far the efforts have been limited, and American officials said that the fact that the C.I.A. took a dim view of its own past efforts to arm rebel forces fed Mr. Obama’s reluctance to begin the covert operation.

“One of the things that Obama wanted to know was: Did this ever work?” said one former senior administration official who participated in the debate and spoke anonymously because he was discussing a classified report. The C.I.A. report, he said, “was pretty dour in its conclusions.”

The debate over whether Mr. Obama acted too slowly to support the Syrian rebellion has been renewed after both former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and former Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta wrote in recent books that they had supported a plan presented in the summer of 2012 by David H. Petraeus, then the C.I.A. director, to arm and train small groups of rebels in Jordan.

Mr. Obama rejected that plan, but in the months that followed, Obama administration officials continued to debate the question of whether the C.I.A. should arm the rebels. Mr. Petraeus’s original plan was reworked until Mr. Obama signed a secret order authorizing the covert training mission after intelligence agencies concluded that President Bashar al-Assad of Syria had used chemical weapons against opposition forces and civilians.

Although Mr. Obama originally intended the C.I.A. to arm and train the rebels to fight the Syrian military, the focus of the American programs has shifted to training the rebel forces to fight the Islamic State, an enemy of Mr. Assad.

The C.I.A. review, according to several former American officials familiar with its conclusions, found that the agency’s aid to insurgencies had generally failed in instances when no Americans worked on the ground with the foreign forces in the conflict zones, as is the administration’s plan for training Syrian rebels.

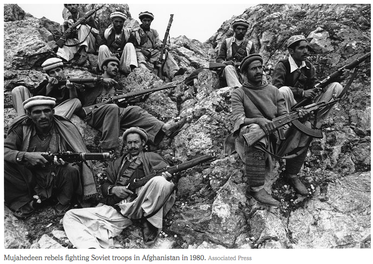

One exception, the report found, was when the C.I.A. helped arm and train mujahedeen rebels fighting Soviet troops in Afghanistan during the 1980s, an operation that slowly bled the Soviet war effort and led to a full military withdrawal in 1989. That covert war was successful without C.I.A. officers in Afghanistan, the report found, largely because there were Pakistani intelligence officers working with the rebels in Afghanistan.

But the Afghan-Soviet war was also seen as a cautionary tale. Some of the battle-hardened mujahedeen fighters later formed the core of Al Qaeda and used Afghanistan as a base to plan the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. This only fed concerns that no matter how much care was taken to give arms only to so-called moderate rebels in Syria, the weapons could ultimately end up with groups linked to Al Qaeda, like the Nusra Front.

“What came afterwards was impossible to eliminate from anyone’s imagination,” said the former senior official, recalling the administration debate about whether to arm the Syrian rebels.

Mr. Obama made a veiled reference to the C.I.A. study in an interview with The New Yorker published this year. Speaking about the dispute over whether he should have armed the rebels earlier, Mr. Obama told the magazine: “Very early in this process, I actually asked the C.I.A. to analyze examples of America financing and supplying arms to an insurgency in a country that actually worked out well. And they couldn’t come up with much.”

Bernadette Meehan, a spokeswoman for the National Security Council, said that “without characterizing any specific intelligence products, the president was referring to the fact that providing money or arms alone to an opposition movement is far from a guarantee of success.”

“We have been very clear about that from the outset as we have articulated our strategy in Syria,” Ms Meehan said. “That is why our support to the moderate Syrian opposition has been deliberate, targeted and, most importantly, one element of a multifaceted strategy to create the conditions for a political solution to the conflict.”

Arming foreign forces has been central to the C.I.A.'s mission from its founding, and was a staple of American efforts to wage proxy battles against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The first such operation was in 1947, the year of the agency’s creation, when President Harry S. Truman ordered millions of dollars’ worth of guns and ammunition sent to Greece to help put down a Communist insurgency there. In a speech before Congress in March of that year, Mr. Truman said the fall of Greece could destabilize neighboring Turkey, and “disorder might well spread throughout the entire Middle East.”

That mission helped shore up the fragile Greek government. More frequently, however, the C.I.A. backed insurgent groups fighting leftist governments, often with calamitous results. The 1961 Bay of Pigs operation in Cuba, in which C.I.A.-trained Cuban guerrillas launched an invasion to fight Fidel Castro’s troops, ended in disaster. During the 1980s, the Reagan administration authorized the C.I.A. to try to bring down Nicaragua’s Sandinista government with a secret war supporting the contra rebels, who were ultimately defeated.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, C.I.A. paramilitary officers and Army Special Forces teams fought alongside Afghan militias to drive Taliban forces out of the cities and set up a new government in Kabul. In 2006, the C.I.A. set up a gunrunning operation to arm a group of Somali warlords who united under the Washington-friendly name the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counterterrorism. That effort backfired, strengthening the Islamist fighters that the C.I.A. had intervened to defeat.

“It’s a very mixed history,” said Loch K. Johnson, a professor of public and international affairs at the University of Georgia and an intelligence expert. “You need some really good, loyal people on the ground ready to fight.”

The progress of the Syrian conflict has only deepened skepticism about the loyalties — and the capabilities — of the Syrian opposition. Years of a bloody civil war have splintered the forces fighting the Assad government’s troops, with an increasing number of fighters pledging loyalty to radical groups like the Islamic State and the Nusra Front.

Last month, Mr. Obama said he would redouble American efforts by having the Pentagon participate in arming and training rebel forces. That program has yet to begin.

Rear Adm. John Kirby, the Pentagon spokesman, said last week that it would be months of “spade work” before the military had determined how to structure the program and how to recruit and vet the rebels.

“This is going to be a long-term effort,” he said.

By MARK MAZZETTI OCT. 14, 2014

(To read the story on NYT website, click here)

WASHINGTON — The Central Intelligence Agency has run guns to insurgencies across the world during its 67-year history — from Angola to Nicaragua to Cuba. The continuing C.I.A. effort to train Syrian rebels is just the latest example of an American president becoming enticed by the prospect of using the spy agency to covertly arm and train rebel groups.

An internal C.I.A. study has found that it rarely works.

The still-classified review, one of several C.I.A. studies commissioned in 2012 and 2013 in the midst of the Obama administration’s protracted debate about whether to wade into the Syrian civil war, concluded that many past attempts by the agency to arm foreign forces covertly had a minimal impact on the long-term outcome of a conflict. They were even less effective, the report found, when the militias fought without any direct American support on the ground.

The findings of the study, described in recent weeks by current and former American government officials, were presented in the White House Situation Room and led to deep skepticism among some senior Obama administration officials about the wisdom of arming and training members of a fractured Syrian opposition.

But in April 2013, President Obama authorized the C.I.A. to begin a program to arm the rebels at a base in Jordan, and more recently the administration decided to expand the training mission with a larger parallel Pentagon program in Saudi Arabia to train “vetted” rebels to battle fighters of the Islamic State, with the aim of training approximately 5,000 rebel troops per year.

So far the efforts have been limited, and American officials said that the fact that the C.I.A. took a dim view of its own past efforts to arm rebel forces fed Mr. Obama’s reluctance to begin the covert operation.

“One of the things that Obama wanted to know was: Did this ever work?” said one former senior administration official who participated in the debate and spoke anonymously because he was discussing a classified report. The C.I.A. report, he said, “was pretty dour in its conclusions.”

The debate over whether Mr. Obama acted too slowly to support the Syrian rebellion has been renewed after both former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and former Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta wrote in recent books that they had supported a plan presented in the summer of 2012 by David H. Petraeus, then the C.I.A. director, to arm and train small groups of rebels in Jordan.

Mr. Obama rejected that plan, but in the months that followed, Obama administration officials continued to debate the question of whether the C.I.A. should arm the rebels. Mr. Petraeus’s original plan was reworked until Mr. Obama signed a secret order authorizing the covert training mission after intelligence agencies concluded that President Bashar al-Assad of Syria had used chemical weapons against opposition forces and civilians.

Although Mr. Obama originally intended the C.I.A. to arm and train the rebels to fight the Syrian military, the focus of the American programs has shifted to training the rebel forces to fight the Islamic State, an enemy of Mr. Assad.

The C.I.A. review, according to several former American officials familiar with its conclusions, found that the agency’s aid to insurgencies had generally failed in instances when no Americans worked on the ground with the foreign forces in the conflict zones, as is the administration’s plan for training Syrian rebels.

One exception, the report found, was when the C.I.A. helped arm and train mujahedeen rebels fighting Soviet troops in Afghanistan during the 1980s, an operation that slowly bled the Soviet war effort and led to a full military withdrawal in 1989. That covert war was successful without C.I.A. officers in Afghanistan, the report found, largely because there were Pakistani intelligence officers working with the rebels in Afghanistan.

But the Afghan-Soviet war was also seen as a cautionary tale. Some of the battle-hardened mujahedeen fighters later formed the core of Al Qaeda and used Afghanistan as a base to plan the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. This only fed concerns that no matter how much care was taken to give arms only to so-called moderate rebels in Syria, the weapons could ultimately end up with groups linked to Al Qaeda, like the Nusra Front.

“What came afterwards was impossible to eliminate from anyone’s imagination,” said the former senior official, recalling the administration debate about whether to arm the Syrian rebels.

Mr. Obama made a veiled reference to the C.I.A. study in an interview with The New Yorker published this year. Speaking about the dispute over whether he should have armed the rebels earlier, Mr. Obama told the magazine: “Very early in this process, I actually asked the C.I.A. to analyze examples of America financing and supplying arms to an insurgency in a country that actually worked out well. And they couldn’t come up with much.”

Bernadette Meehan, a spokeswoman for the National Security Council, said that “without characterizing any specific intelligence products, the president was referring to the fact that providing money or arms alone to an opposition movement is far from a guarantee of success.”

“We have been very clear about that from the outset as we have articulated our strategy in Syria,” Ms Meehan said. “That is why our support to the moderate Syrian opposition has been deliberate, targeted and, most importantly, one element of a multifaceted strategy to create the conditions for a political solution to the conflict.”

Arming foreign forces has been central to the C.I.A.'s mission from its founding, and was a staple of American efforts to wage proxy battles against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The first such operation was in 1947, the year of the agency’s creation, when President Harry S. Truman ordered millions of dollars’ worth of guns and ammunition sent to Greece to help put down a Communist insurgency there. In a speech before Congress in March of that year, Mr. Truman said the fall of Greece could destabilize neighboring Turkey, and “disorder might well spread throughout the entire Middle East.”

That mission helped shore up the fragile Greek government. More frequently, however, the C.I.A. backed insurgent groups fighting leftist governments, often with calamitous results. The 1961 Bay of Pigs operation in Cuba, in which C.I.A.-trained Cuban guerrillas launched an invasion to fight Fidel Castro’s troops, ended in disaster. During the 1980s, the Reagan administration authorized the C.I.A. to try to bring down Nicaragua’s Sandinista government with a secret war supporting the contra rebels, who were ultimately defeated.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, C.I.A. paramilitary officers and Army Special Forces teams fought alongside Afghan militias to drive Taliban forces out of the cities and set up a new government in Kabul. In 2006, the C.I.A. set up a gunrunning operation to arm a group of Somali warlords who united under the Washington-friendly name the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counterterrorism. That effort backfired, strengthening the Islamist fighters that the C.I.A. had intervened to defeat.

“It’s a very mixed history,” said Loch K. Johnson, a professor of public and international affairs at the University of Georgia and an intelligence expert. “You need some really good, loyal people on the ground ready to fight.”

The progress of the Syrian conflict has only deepened skepticism about the loyalties — and the capabilities — of the Syrian opposition. Years of a bloody civil war have splintered the forces fighting the Assad government’s troops, with an increasing number of fighters pledging loyalty to radical groups like the Islamic State and the Nusra Front.

Last month, Mr. Obama said he would redouble American efforts by having the Pentagon participate in arming and training rebel forces. That program has yet to begin.

Rear Adm. John Kirby, the Pentagon spokesman, said last week that it would be months of “spade work” before the military had determined how to structure the program and how to recruit and vet the rebels.

“This is going to be a long-term effort,” he said.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed